The enforcement of adverse impact — legally known as disparate impact — has changed due to an April 2025 executive order. Here, we review the history, definition, and relevance of adverse impact in hiring today.

What you should know

- Adverse impact occurs when seemingly neutral hiring practices — like physical ability or cognitive tests — disproportionately exclude protected groups (like women or racial minorities), even without intending to.

- The EEOC enforces Title VII of the Civil Rights Act and measures adverse impact using the UGESP and tools like the Four-Fifths rule. However, due to EO 14281, the EEOC may relax enforcement of disparate impact clauses.

- To prevent adverse impact regardless, employers should use validated, job-relevant skills tests and structured interviews — and be cautious with AI tools, which can both reduce or exacerbate bias. Fair, skills-based hiring not only ensures legal compliance but also broadens talent pools.

Let’s rewind to February, 2000. Y2K panic has just fizzled out. Blockbuster is booming. NSYNC and Britney are playing in every mall. You’re a woman in your mid-40s, by the way — wearing bootcut jeans with a flip phone clipped to your belt. And you just applied to work at Dial Corp. — yes, the soap company. But not in a soap factory — you applied to work at a meatpacking plant owned by the company that owns Dial.

You’ve done similar work before, so you’re expecting to get hired without a hitch.

You get through the interviews and the written portion of the applicant process. But before you’re officially hired, you’re instructed to take a physical ability test, asking you to lift a 35-pound rod of weights (on the job, they would be sausages) above your head repeatedly. Unfortunately, you’re a little short, so to reach up to the required height of 67 inches, you have to get on your tippy-toes. You technically pass the seven-minute test, but the company still doesn’t hire you.

But wait a minute — it’s not just you. A lot of other women applying are failing the “physical ability” test, too. While men are passing the test 97% of the time, women are passing and getting hired at less than half that rate.

That’s funny when you consider that in the years before the test was implemented, nearly half of the people being hired at the sausage plant were women. What’s the deal?

In 2005, the federal court found in Dial Corp. v. EEOC that Dial’s use of its physical ability test intentionally discriminated against women, rejecting its validity. The EEOC maintained that the test was unfair to female candidates because it was unnecessarily harder than what would be expected for actual performance in the role.

This court case demonstrates a crucial concept in hiring: disparate impact (also called “adverse impact,” depending on the context).

There are far more cases out there — way beyond this on-the-nose example of a sausage factory that won’t hire women. However, the implications of adverse impact have changed this year with the signing of an April executive order, guiding federal agencies to deprioritize cases where disparate impact is concerned.

Regardless, protecting against disparate impact is still on the minds of hiring managers, as they not only protect against legal problems, but can also broaden talent pools and ensure better, quicker hiring. After all, there’s no sure bet that this executive order will last into the next administration, or the one after that.

So is adverse impact still a problem, and should hiring managers still care? Before we get into the details, let’s start with a definition.

The definition of adverse impact in hiring

Adverse impact, also known as disparate impact, is a legal (and statistical) concept in hiring. It refers to when a seemingly neutral hiring practice disproportionately harms members of a protected group (such as by race, sex, age, or national origin) — even if there's no intent to discriminate.

A key point of adverse impact is that it’s about outcomes, not intent. A practice can cause adverse impact even if it wasn’t meant to discriminate. A practice that is intending to discriminate, on the other hand, is referred to as disparate treatment.

Because it’s done without intent, adverse impact can be particularly insidious. On the surface, many tests and practices don’t seem discriminatory. But in reality, something like a simple physical assessment (like the test used by Dial) can disproportionately — and unfairly — screen out certain demographics.

What are some examples of adverse impact?

It’s important to note that for a test to demonstrate adverse impact, it must not be relevant to the job at hand and no alternative test should exist that could replace it.

Examples of adverse impact could include:

- A physical ability test that excludes women more than men (like with Dial).

- A cognitive test that disproportionately screens out candidates from certain racial backgrounds.

- Requiring a college degree for an entry-level job where it’s not actually necessary — which may disadvantage lower-income applicants. Many states and cities — including the City of Chicago — have moved toward implementing skills-based hiring at the government level.

Situations like these could lead to adverse impact claims, and they have in the past.

However, these may not qualify as adverse impact if the tests demonstrate a BFOQ. A bona fide occupational qualification (BFOQ) is a legally recognized exception to anti-discrimination laws in employment.

It allows employers to consider certain characteristics like sex, religion, or national origin when making hiring decisions, but only if those characteristics are reasonably necessary to the normal operation of the business — for example, a Catholic church could require its clergy to be Catholic. The employer must have also considered and rejected less discriminatory alternatives that still meet the job requirement.

However, it’s important to note that BFOQs are narrowly construed. The employer bears the burden of proving the BFOQ is legitimate.

Let’s look at the above examples again.

- If the job is for a firefighter and the test assesses the ability to carry heavy loads up stairs under timed conditions — and that’s essential to the role — a physical ability test might be allowed, even if it excludes more women.

- A cognitive test that disproportionately screens out candidates from certain racial backgrounds would not qualify as adverse impact if the test is valid and predictive of job performance, is clearly job-related, and there’s strong empirical validation showing a high correlation between test scores and success on the job. Additionally, no less discriminatory yet equally effective alternative should exist. That’s a high bar.

- Requiring a college degree for an entry-level job where it’s not actually necessary would not qualify as adverse impact if the degree requirement can be shown to directly relate to job performance, even for an entry-level role. For example, if the employer can demonstrate a legitimate business necessity — such as the need for employees to have a foundational understanding of a complex field, which a degree typically provides. And again, no less discriminatory alternative (for example, skills-based assessments) would achieve the same hiring goal.

Still, it’s best to do your utmost to prevent cases that could lead to adverse impact. Under the Civil Rights Act of 1991, the employer carries a greater burden of proof in establishing a reason for rejecting a potential employee. The bar for proving BFOQ is high and the burden of proof for demonstrating test validity falls on the employer, not the candidate.

Adverse impact vs. disparate impact

While in this piece we’re using the terms adverse impact and disparate impact mostly interchangeably, there’s an important distinction: disparate impact refers more specifically to legal terminology, while adverse impact is the statistical concept associated with that terminology. We’ll get more into this later.

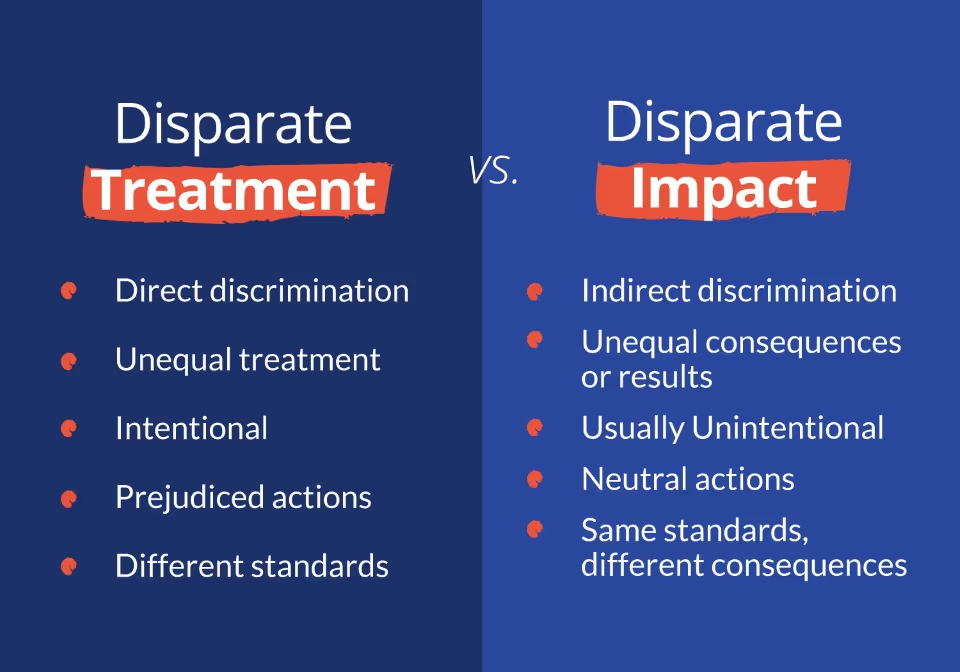

Disparate impact vs. disparate treatment

We briefly touched on adverse impact and disparate impact, but here’s a little more info. Adverse impact and disparate treatment are two distinct types of employment discrimination recognized under U.S. law.

Disparate treatment occurs when an employer intentionally treats someone differently because of a protected characteristic, such as race, gender, or age — for example, refusing to interview women for a leadership role.

Adverse impact (also known as disparate impact), on the other hand, refers to employment practices that appear neutral on the surface but disproportionately exclude members of a protected group, even if unintentional.

While disparate treatment hinges on intent, disparate impact does not — yet both were prohibited under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The legal framework

The legal framework for adverse impact has existed for a while — since 1964, to be exact. With the establishment of the Civil Rights Act, hiring practices have long been required to promote fairness toward all candidates.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is a landmark federal law that prohibits employers from discriminating against individuals based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It applies to employers with 15 or more employees, including federal, state, and local governments, as well as employment agencies and labor organizations.

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.

Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1971) is one of the most important U.S. Supreme Court cases on employment discrimination and the legal foundation for the concept of disparate (or adverse) impact under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The outcome made clear that intent to discriminate is not required to establish a violation — outcomes matter, and employers must ensure that hiring criteria do not unfairly disadvantage protected groups without clear job relevance.

EEOC guidelines

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is the federal agency responsible for enforcing laws that prohibit workplace discrimination. The agency investigates complaints of discrimination, mediates disputes, issues guidance on compliance, and can file lawsuits against employers that violate federal anti-discrimination laws. Its mission is to promote equal opportunity in employment by ensuring that all individuals have fair access to jobs, advancement, and workplace protections regardless of race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, disability, or genetic information.

In 1978, the EEOC adopted the Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures or “UGESP” under Title VII.

The Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures (UGESP)

The Uniform Guidelines of Employee Selection Procedures establishes uniform standards for employers for the use of selection procedures and to address adverse impact, validation, and record-keeping requirements. It’s essentially a uniform federal position in the area of prohibiting discrimination in employment practices. The UGESP applies to all selection procedures used to make employment decisions — that includes interviews, review of experience or education from application forms, work samples, physical requirements, and evaluations of performance.

Civil Rights Act of 1991

The Civil Rights Act of 1991 was enacted to strengthen and expand the protections established under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, particularly in the context of employment discrimination. It clarified and reinforced the legal standards for proving disparate impact. The act shifted more of the burden of proof onto employers, requiring them to demonstrate that a challenged employment practice is job-related and consistent with business necessity.

April 2025 Executive Order

With EO 14281, the administration ordered federal agencies — including the EEOC — to deprioritize enforcement of disparate impact claims, instead emphasizing a merit-based approach that treats people as “individuals” rather than part of racial, sex, or other demographic groups.

This executive order builds on Trump's January 2025 actions cutting back DEI programs and rescinding federal affirmative-action orders (e.g., EO 14173, 11246, and related ones) — but has an altogether different scope, since it specifically targets disparate impact. The executive order mandates that federal enforcement only continues based on disparate treatment, which must show more blatantly an intent to discriminate.

Somewhat surprisingly, the executive order also calls on the Attorney General and the Chair of the EEOC to issue guidance and assistance to employers “regarding appropriate methods to promote equal access to employment regardless of whether an applicant has a college education, where appropriate.”

How adverse impact is measured: the four-fifths rule

Like we’ve mentioned, adverse impact is a statistical measurement used to determine disparate impact. Under the UGESP, adverse impact is most commonly measured using the four-fifths rule.

According to this rule, if the selection rate for any race, sex, or ethnic group is less than 80% (or four-fifths) of the rate for the group with the highest selection rate, adverse impact may be present.

However, the rule is a guideline — not a legal threshold — and further statistical analysis may be needed to confirm whether the impact is significant. Some practitioners have moved away from this rule in the twenty-first century.

Common Causes of Adverse Impact

There are a few tools used in interview processes that have repeatedly come under fire for causing disparate impact, among which are cognitive ability tests, unstructured interviews, and degree requirements. Below, we’ll look at these concepts as well as a few cases in which complaints of adverse impact have led to cases, and how they played out in court.

Cognitive ability tests

Generalized cognitive ability tests used to be cited as a good predictor of job success, but they may not be the answer to your hiring woes. In fact, they’re the first interview tools that led to the landmark case that established the meaning of disparate impact in the first place: Griggs v. Duke Power Co. in 1971.

Unlike relevant hard skills tests, with general cognitive ability tests, it’s difficult to prove relevance to the role at hand, making the threat of leading to adverse impact more of a risk.

Customized vs. standard tests

In order to avoid claims of disparate impact (and lead to the best hires), pre-hire tests must always, always demonstrate relevance to the job at hand. That’s why customized testing will always work better when compared to straight-out-of-the-box, one-size-fits-all tests. This is especially true when you’re testing aptitude-based skills, like cognitive ability or attention to detail.

Here’s a relevant legal case.

U.S. v. City of New York (FDNY)

In U.S. v. City of New York, the DOJ and EEOC sued New York City over their fire department’s 2002 and 2007 written entrance exams, which disproportionately excluded Black and Hispanic candidates. The courts found the tests lacked content validity and had no strong link to actual firefighting duties or success. Because the exams had a discriminatory impact and were not job-related, NYC was ordered to pay millions in back pay and revise its hiring practices.

Unstructured interviews

Unstructured interviews not only fail to predict job success reliably — they also open the door to bias, especially affinity bias. Because they lack standardization, they’re difficult to defend legally and nearly impossible to document consistently. In short, unstructured interviews make for a poor hiring benchmark on every front.

Watson v. Fort Worth Bank & Trust (1988)

The Supreme Court case Watson v. Fort Worth Bank & Trust (1988) illustrates this risk clearly. A Black female employee was denied a promotion based on subjective interviews and managerial discretion. The Court ruled that subjective decision-making could be challenged under a disparate impact theory — not just disparate treatment. This landmark decision expanded the legal grounds for scrutinizing subjective hiring and promotion practices.

Degree requirements

Requiring a high school or college degree for roles that don’t actually demand them can unintentionally create adverse impact — particularly for candidates from historically marginalized groups who may have had less access to formal education.

This issue remains highly relevant today, as both public and private sectors increasingly embrace skills-based hiring. In fact, it’s one of the few workforce policy initiatives with bipartisan support in the U.S., with state and federal governments moving to eliminate unnecessary degree requirements from job postings.

How to Prevent Adverse Impact

Adverse impact should be on your radar. It’s just good practice to maintain an equitable hiring process.

Use relevant assessments

The easiest way to prevent adverse impact is to first make sure pre-hire assessments are relevant to the job at hand.

The most relevant tests? The ones assessing hard skills related to on-the-job abilities. They’re far more predictive of hiring performance than cognitive ability assessments, personality tests, and EQ tests.

Conduct a job analysis

Conducting a job analysis helps mitigate adverse impact by ensuring that hiring criteria are directly tied to the actual knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) required for a specific role.

By systematically identifying the essential functions and qualifications needed for job performance, employers can design assessments and selection procedures that are job-related and consistent with business necessity. This reduces the likelihood of using arbitrary or biased selection tools that disproportionately exclude protected groups.

Structure your interviews

Unstructured interviews can open the door to bias. Structured interviews help mitigate bias by ensuring all candidates are measured by the same rubric, using the same questions. When done correctly, structured interviews are the topmost relevant predictors of job performance.

The Role of Technology and AI

AI-powered hiring decisions can promote diversity and inclusion if used properly, but as technology develops, the risk of disparate impact is unknown in some populations and can be risky for some organizations.

How automated tools can create or mitigate bias

AI hiring tools have already come under fire for potentially causing bias in recruiting. For instance, Amazon famously scrapped an internal recruiting tool after discovering it downgraded resumes that included the word “women’s” (as in “women’s chess club captain”) — because the model had been trained on ten years of resumes that skewed male. Other tools have been found to unfairly favor certain accents, word choices, or facial expressions.

These systems can create adverse impact if they disproportionately screen out candidates from protected groups, even unintentionally.

But AI can also help mitigate bias — if it’s designed with fairness in mind. For example, structured assessments that focus on job-relevant skills rather than resumes can reduce reliance on subjective factors and help level the playing field.

EEOC guidance on algorithmic fairness

The EEOC made it clear: using AI doesn’t absolve employers of responsibility under Title VII. In 2023, the EEOC and the Department of Justice issued joint guidance warning employers that automated tools must still comply with federal civil rights laws. If an AI system causes adverse impact, the employer may be held liable — even if the system was built by a third-party vendor.

The EEOC also encourages employers to audit their tools for bias, maintain transparency about how hiring algorithms work, and provide accommodations for applicants with disabilities.

However, the current administration removed key documents around AI guidance for employers, essentially rolling back these EEOC guidelines. Presumably, AI hiring practices are no longer regulated at the federal level.

While the April executive order and recent federal hiring updates may have changed thinking around these regulations, employers must still be mindful of regulations at the state level, both on AI and on hiring practices.

State-level guidance and regulation

Many states have begun introducing their own laws and guidance around AI in hiring. For example, Illinois requires employers using AI in video interviews to notify applicants and obtain consent. New York City Local Law 144 requires employers to conduct annual bias audits of automated employment decision tools and to publish the results publicly. California, Maryland, and others are exploring or have implemented similar transparency and fairness regulations.

As regulatory scrutiny grows, employers must take a proactive approach — auditing their tools, validating them for job relevance, and ensuring compliance with both federal and local laws.

Why fairness and compliance benefit everyone

Fair hiring practices aren’t just about avoiding lawsuits or ticking boxes. They also create stronger, more effective teams — additionally expanding the talent pool and increasing retention.

Yes, fairness benefits the hiring team, but it also benefits candidates, customers, and the company’s reputation as a whole. Inclusive hiring practices improve morale, support diversity goals, and help organizations tap into underutilized talent.

Skills tests can actually lead to better compliance. When designed and validated correctly, skills tests can align with EEOC Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures (UGESP) and reduce the risk of adverse impact. Especially for roles that previously relied on proxies like college degrees or high school diplomas — which can disproportionately screen out candidates from lower-income or historically marginalized backgrounds — a skills-based assessment can be a more objective and job-relevant alternative.

Does accounting for adverse impact even matter anymore?

Some argue that recent regulatory shifts have made it less risky for employers to use hiring tools that produce biased outcomes — so long as there's no explicit discriminatory intent.

In other words, if a tool leads to unequal results but wasn’t designed with the intent to discriminate, employers may face fewer federal consequences. This relaxed enforcement posture could lower compliance burdens for AI vendors and HR teams alike.

But it also raises serious concerns: without strong incentives to audit tools for fairness, there’s a greater risk of reinforcing systemic bias, overlooking qualified candidates, and ultimately damaging both reputation and workforce diversity.

At eSkill, we want everyone to have a fair chance at a role. That’s why we spearhead relevant skills-based hiring. It shouldn’t matter who you know, what your resume says, what school you went to — do you have the skills to get the job done? We shine the spotlight on fair, hard- skills-based hiring for employers — with as little risk for adverse impact as possible.

Flash forward to 2055. You’re a woman in your mid-40s again. You can stream movies straight from your contact lenses. Your smartphone is actually a chip embedded in your brain. And you’re now the VP of People Operations at a clean-meat startup that makes lab-grown brisket for space missions. And you’ve just paused your morning haptic pilates to review a flagged hiring dashboard.

One of your team’s new screening tools — a gamified “reaction time” test for production roles — is showing unexpected results: neurodivergent candidates are failing it at twice the rate of others, despite excelling in the same roles during on-the-job assessments.

You pause. Déjà vu. It’s not a 35-pound sausage rod anymore, but the impact feels familiar.

And just like in 2000, the question isn’t just “Is this test legal?”

It’s also “Is it fair? Is it necessary? Is it filtering out the talent we actually need?”

Relevant, skills-based assessments will always be, well, relevant.

Get ademo.